Publication

Related Platypus content

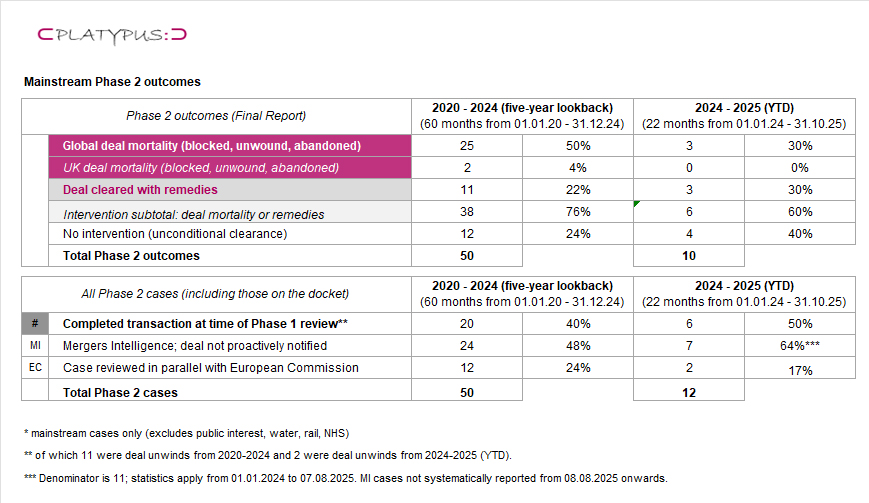

On our Platypus page, we present key statistics showing the UK Competition and Market Authority’s evolving approach to merger control. We combine this with periodic commentary and case analysis drawing on our team’s experience on many of the biggest UK merger control investigations in recent years.

Click on the link for our analysis on Phase I outcomes

Click on the link for our analysis on CMA Fines in Merger Control cases